The Perl distribution comes with a number of standard Perl library functions and packages. The Perl 4 library routines are procedural programs and their names end in a .pl extension. The Perl 5 modules end with a .pm extension. In Perl 5, the .pm files are called modules. The .pm files are modules written in two programming styles: procedural and object oriented. The module filenames start with a capital letter. The .pm filenames starting with a lowercase letter are a special type of module, called a pragma. A pragma is a module that tells the compiler that certain conditions must be checked in a Perl program before it can run. Files that have no extension at all are subdirectories. They contain common modules that are divided into several .pm files; for example, the Math subdirectory contains BigFloat.pm, BigInt.pm, Complex.pm, and Trig.pm.

Here is a sample listing from the standard Perl 5 library:[2]

[2] The pathname to the standard Perl library is determined at the time Perl is installed. This can be assigned either a default value or a pathname designated by the person installing Perl.

AutoLoader.pm

AutoSplit.pm

B

B.pm

Benchmark.pm

ByteLoader.pm

CGI

CGI.pm

CORE

CPAN

CPAN.pm

Carp

Carp.pm

Class

Config.pm

Config.pm~

Cwd.pm

DB.pm

Data

Devel

DirHandle.pm

Dumpvalue.pm

DynaLoader.pm

English.pm

Env.pm

Errno.pm

Exporter

Exporter.pm

ExtUtils

Fatal.pm

Fcntl.pm

File

FileCache.pm

FileHandle.pm

FindBin.pm

Getopt

I18N

IO

IO.pm

IPC

Math

Net

O.pm

Opcode.pm

POSIX.pm

POSIX.pod

Pod

SDBM_File.pm

Safe.pm

Search

SelectSaver.pm

SelfLoader.pm

Shell.pm

Socket.pm

Symbol.pm

Sys

Term

Test

Test.pm

Text

Thread

Thread.pm

Tie

Time

UNIVERSAL.pm

User

XSLoader.pm

abbrev.pl

assert.pl

attributes.pm

attrs.pm

auto

autouse.pm

base.pm

bigfloat.pl

bigint.pl

bigrat.pl

blib.pm

bytes.pm

bytes_heavy.pl

cacheout.pl

charnames.pm

chat2.pl

complete.pl

constant.pm

ctime.pl

diagnostics.pm

dotsh.pl

dumpvar.pl

exceptions.pl

fastcwd.pl

fields.pm

filetest.pm

find.pl

finddepth.pl

flush.pl

ftp.pl

getcwd.pl

getopt.pl

getopts.pl

hostname.pl

importenv.pl

integer.pm

less.pm

lib.pm

locale.pm

look.pl

network.pl

newgetopt.pl

open.pm

open2.pl

open3.pl

ops.pm

overload.pm

perl5db.pl

perllocal.pod

ppm.pm

pwd.pl

re.pm

shellwords.pl

sigtrap.pm

stat.pl

strict.pm

subs.pm

syslog.pl

tainted.pl

termcap.pl

timelocal.pl

unicode

utf8.pm

utf8_heavy.pl

validate.pl

vars.pm

warnings

warnings.pm

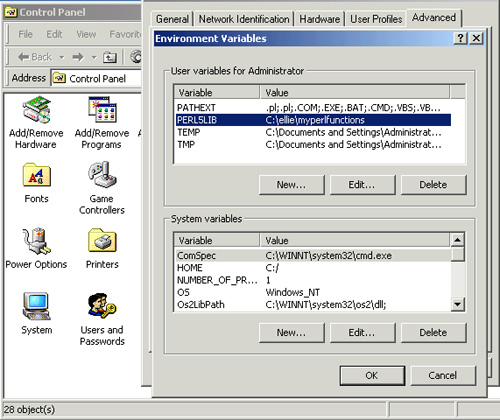

The special array @INC contains the directory path to where the library routines are located. To include directories not in the @INC array, you can use the -I switch[3] at the command line, or set the PERL5LIB environment variable to the full pathname. Normally, this variable is set in one of your shell initialization files, either .login or .profile if using UNIX. See Figure 12.4 if using Windows.

[3] See Table A.18 in Appendix A for a description of the -I switch.

If you are using UNIX/Linux operating systems, to add new path elements to the @INC array, the PERL5LIB environment variable can be set in your startup initialization files.

In .login for the C and TC shells:

setenv PERL5LIB "directory path"

In .profile for the Bourne, Korn, and Bash shells:

PERL5LIB="directory path"; export PERL5LIB

If you are using Windows, go to the Start menu, then to Settings, then System Properties, then Environment Variables, and finally New. Refer back to Figure 12.4.

To give your own library routines precedence over those in listed in the @INC array, you can put the following line in your program:

unshift(@INC,".");

Unshift causes the . to be prepended to the @INC array, making your present working directory the first element in the search path. If your library is in a different directory, use its full pathname rather than the dot.

Most of the library routines found in the standard Perl library ending in .pl were written in the Perl 4 days. They consisted of subroutines contained within a package. The library files are still available but have largely been replaced with modules or .pm files.

In order to include and execute routines from the standard Perl library (specifically .pl files) or Perl code from any other file, the require function can be used, which is similar to the C #include statement. The require function checks to see if the library has already been included, unlike the eval and the do functions, which are older methods for including files. Without an argument, the value of $_ is included. If the @INC array does not have the correct path to the library, the require will fail with a message such as the following:

Can't locate pwd.pl in @INC at package line 3.

The require function loads files into the program during runtime. The @INC array is also updated at runtime.

Formatrequire (Expr) require Expr require |

To see an example of a library routine in Perl's library, the pwd.pl routine (written by Larry Wall) is shown in Example 12.5. The pwd package consists of two subroutines that update the PWD environment variable after the chdir function has been executed. The value of $ENV{PWD} is the present working directory.

Notice that in the following Perl library function, the package pwd is declared before the subroutines are defined, thus placing the rest of the file within the pwd package. All variables belong to the package. The names of the subroutines are explicitly switched to package main. They may be called from your main package, but the variables remain local to the pwd package. (The apostrophe is used here instead of the two colons to switch namespaces. The apostrophe is the Perl 4 symbol for switching namespaces.)

The following example is a sample .pl routine from Perl's standard library.

The following example uses a library routine in the script.

The following example shows you how to create your own library functions and include them into a Perl script with the require function. When including user-defined routines or adding routines to a library, make sure to include 1; (a nonzero value) as the last line of the routine. If you do not return a true value as the last line of your library file, this is the type of error you will get from the require function:

average.pl did not return a true value at user.plx line 3.

When using one of the modules (those files ending in .pm) provided in the standard Perl library, you must first make sure the @INC array contains the full pathname to your library distribution and that you include the use function with the module name.

If you are trying to find out how a particular library module works, you can use the perldoc command to get the documentation. (The perldoc command does not work for .pl files from the library.) For example, if you want to know about the CGI.pm module, type at the command line

perldoc CGI

and the documentation for the CGI.pm module will be displayed. If you type

perldoc English

the documentation for the English.pm module will be displayed.

The use function allows Perl modules and pragmas to be imported into your program at compile time. The use function will not import a module if the module's filename does not have the .pm extension. The require function does the same thing but does not do imports and loads the module at runtime.

A module is a file in a library that behaves according to certain set of conventions. The modules in the standard Perl library are suffixed with the .pm extension. They can also be found in subdirectories. For example, the module Bigfloat.pm is found in a subdirectory called Math. To use a module found in a subdirectory, the directory name is followed by two colons and the name of the module, such as Math::Bigfloat.pm. (Although using the two colons makes it appear that Bigfloat.pm is in a package called "Math," in this context the two colons are used to separate the Math directory/folder from the module. The colon then will be translated to a forward slash for UNIX-type operating systems and a backslash for Windows sytems.)

A pragma, spelled in lowercase letters, is a directive to the compiler that your program should behave in a certain way and, if it doesn't, the program will abort. Some common pragmas are lib, strict, subs, and diagnostics. For a list of modules and pragmas, see Tables A.4 and A.5 in Appendix A.

In object-oriented terminology, subroutines are called methods. If you receive diagnostics using the term method, for now just think of methods as glorified subroutines. Many of the modules in the library use object-oriented Perl. The modules discussed in this chapter do not require any understanding of objects. For a complete discussion on how to use the object-oriented modules, see Chapter 14, "Bless Those Things! (Object-Oriented Perl)."

Formatuse Module; use Module ( list ); use Directory::Module; use pragma (list); no pragma; |

In the export/import business, someone exports his goods and the someone who imports them is waiting on the other side. Let's say a wine maker in California has four great-tasting wines in his cellar, and he decides to export three of the wines to buyers but keep the best ones for himself. So he creates an export list and tacks it to the wall of his cellar, and, when the buyer comes, the buyer selects only those wines on the export list. The buyer is the importer. There's nothing preventing the importer from taking all four of the wines, but if he follows the guidelines of the export list, he will take only those listed.

When you use a Perl module, you are like the buyer. You import symbols (subroutines, variables, etc.) from the export list provided by the module. You take symbols from another package and add them to your own symbol table. You can take what's on the export list by default, you can ask for specific symbols from the list, or you can even exclude some or all of the symbols on the list. The business of exporting and importing is really just a way of getting symbols into the namespace of your program package so you don't have to fully qualify all the imported names with the module package name and two colons, such as Module::fun1. What you import can be listed after the use directive, such as use Module qw(fun1 fun2);.

The exporting module sends symbols to the user of the module. The Exporter.pm module found in the standard Perl library supplies the necessary semantics for modules to be able to export symbols. It implements an import method that allows a module to export functions and variables to its users' namespaces. As we discussed earlier, symbols are stored as a hash of typeglobs on the symbol table for the package. The import routine creates an alias for the symbol that is being taken from one package and used in another. Consider the statement:

*Package_mine::somefunction = \&Package_exporter::somefunction

The package called "Package_mine" is importing a symbol called "somefunction" from "Package_exporter". The symbol is the name of a subroutine called "somefunction". A reference to "somefunction" in the exporting package is assigned to a typeglob in "Package_mine"; i.e., put on the symbol table of "Package_mine".

The Exporter module implements an import routine that uses similar semantics as shown previously. Although you can write your own import function, many modules use Exporter because it provides a highly flexible interface and is easy to use.

Perl automatically calls the import method when processing a use statement for a module. Modules and use are documented in perlfunc and perlmod. Understanding the concept of modules and how the use statement operates is important to understanding the Exporter. The Exporter.pm module is an object-oriented module that functions as a class. Other modules inherit from the Exporter class the capability to export symbols. (See Chapter 14 for more on object-oriented programs.) Inherited classes must be listed in the @ISA array.

require Exporter; our @ISA=qw(Exporter);[4]

[4] Note that the Exporter module is not enclosed in double quotes when used as an argument to require and that .pm is missing. This tells the compiler two things: if, for example, the module is Math::BigFloat, that will be translated to Math/BigFloat, and if there are indirect method calls within the module, they will be treated as object-oriented method calls, not ordinary subroutine calls.

The names listed in the @EXPORT array are by default switched into the namespace of the program using the module; the names on the @EXPORT_OK array are added to the user's namespace only if requested. The @EXPORT_FAIL array lists those symbols that cannot be exported. The %EXPORT_TAGS hash contains groups of symbols. If the module is imported with use and parentheses are added to the module name, as in use Module(), none of the symbols is exported to the module. Table 12.1 describes the exporting modules and the users of the modules.

| The Exporting Module | What It Means |

| package Testmodule; | Package declaration. |

| require Exporter; | Use the Exporter.pm module to export symbols from package to package. |

| our @ISA = qw(Exporter); | @ISA contains the names of base classes needed to do the exporting. |

| our @EXPORT = qw($x @y z); | Symbols in this list are automatically exported to the user of this module. |

| our @EXPORT_OK = qw(fun b c); | Symbols in this list are exported only if requested by the user of this module. |

| our @EXPORT_FAIL=qw(fun3 e); | These symbols are not to be exported.[a] |

| our %EXPORT_TAGS= ( ':group1' => [ qw( a b c ) ], ':group2' => [qw( $x @y %c ) ] ); | The key ':group1' represents the symbols a, b, and c (function names), collectively; ':group2' represents the symbols $x, @y, and %c, collectively. |

| The Importing Module | What It Means |

| use Testmodule; | Testmodule is loaded. |

| use Testmodule qw( fun2 ); | Testmodule is loaded; fun2 is imported. |

| use Testmodule(); | Testmodule is loaded, no symbols imported. |

| use Testmodule qw(:group1 !:group2 ); | Testmodule imports symbols from group1 (See:%EXPORT_TAGS hash, above) but not symbols from group2. |

| use Testmodule qw(:group1 !fun2); | Testmodule imports symbols from group1, not the symbol fun2. |

| use Testmodule qw(/^fu/); | Testmodule imports symbols whose names start with fu. |

| SomeModule.pm | User of the Module |

| package SomeModule.pm; | use SomeModule; |

| use Exporter; our @ISA = qw(Exporter); our @EXPORT=qw(a b c); sub a { } sub b { } sub c { } sub d { } 1; | &a; &b; &c; # functions and variables automatically # imported from the @EXPORT array &SomeModule::d; # d isn't on the @EXPORT list; # its name must be fully qualified |

| package SomeModule.pm; use Exporter; our @ISA = qw(Exporter); our @EXPORT_OK=qw(a b c); sub a {} sub b {} sub c {} sub d {} 1; | use SomeModule qw(a c); # must ask for symbols &a; # or they won't be imported &c; &SomeModule::c; # must fully qualify names of symbols SomeModule::d; # not asked for from @EXPORT_OK list |

[a] Variables have the funny symbol preceding their name; subroutines don't have a funny symbol. a, b, and c refer to subroutines with those names.

When you are ready to start using Perl modules, you can use the built-in perldoc command to retrieve the documentation from Perl 5 modules that were formatted with special pod directives (see Chapter 15 for details on this type of formatting). The following excerpt was taken from the CGI.pm documentation.

Note: If you are interested in testing the code displayed in the CGI.pm module, cut and paste the following text, highlighted in bold, and put it into a file. Save the file in the cgi-bin directory under your Web server's root. If using UNIX, turn on execute permission with chmod. Then execute the script in your browser. If you are unfamiliar with how to execute CGI programs, go to Chapter 16 in this book for detailed instructions.

|

Code View: (At the Command Line) 1 perldoc CGI (Output) NAME CGI - Simple Common Gateway Interface Class SYNOPSIS # CGI script that creates a fill-out form # and echoes back its values. 2 use CGI qw/:standard/; 3 print header, start_html('A Simple Example'), h1('A Simple Example'), start_form, "What's your name? ",textfield('name'),p, "What's the combination?", p, checkbox_group(-name=>'words', -values=>['eenie','meenie','minie','moe'], -defaults=>['eenie','minie']), p, "What's your favorite color? ", popup_menu(-name=>'color', -values=>['red','green','blue','chartreuse']),p, submit, end_form, hr; if (param()) { my $name = param('name'); my $keywords = join ', ',param('words'); my $color = param('color'); print "Your name is",em(escapeHTML($name)),p, "The keywords are: ",em(escapeHTML($keywords)),p, "Your favorite color is ",em(escapeHTML($color)), hr; } ABSTRACT This perl library uses perl5 objects to make it easy to create Web fill-out forms and parse their contents. This package defines CGI -- More -- Explanation

|

The following module, English.pm, provides aliases for built-in variables, such as $_ and $/. For any variables that are also part of the awk programming language, there are both long and short English names for the variable. For example, the number of the current record is represented as $. in Perl and NR in awk. The English names are either $RS (awk) or $INPUT_RECORD_SEPARATOR (Perl).

The following example is a sample .pm file from Perl's standard library.

|

Code View: (A Module from the Standard Perl Library)[a] 1 package Carp; # This package implements handy routines # for modules that wish to throw # exceptions outside of the current package 2 require Exporter; 3 @ISA = Exporter; 4 @EXPORT = qw(confess croak carp); 5 sub longmess { 6 my $error = shift; my $mess = ""; my $i = 2; my ($pack,$file,$line,$sub); while (($pack,$file,$line,$sub) = caller($i++)) { $mess .= "\t$sub " if $error eq "called"; $mess .= "$error at $file line $line\n"; $error = "called"; } $mess || $error; } sub shortmess { my $error = shift; my ($curpack) = caller(1); my $i = 2; my ($pack,$file,$line,$sub); while (($pack,$file,$line,$sub) = caller($i++)) { return "$error at $file line $line\n" if $pack ne $curpack; } longmess $error; } 7 sub confess { die longmess @_; } 8 sub croak { die shortmess @_; } 9 sub carp { warn shortmess @_; } Explanation

|

[a] The Carp.pm module has been rewritten and is much larger with an additional function, called cluck, but this version is used here because it is easier to see how the exporting of subroutines works.

The following example demonstrates how to use the Carp module from the standard Perl library. The first step in using a module is to read the documentation. This can be done with the perldoc command.

$ perldoc Carp NAME carp - warn of errors (from perspective of caller) cluck - warn of errors with stack backtrace (not exported by default) croak - die of errors (from perspective of caller) confess - die of errors with stack backtrace shortmess - return the message that carp and croak produce longmess - return the message that cluck and confess produce SYNOPSIS use Carp; croak "We're outta here!"; use Carp qw(cluck); cluck "This is how we got here!"; print FH Carp::shortmess("This will have caller's details added"); print FH Carp::longmess("This will have stack backtrace added"); DESCRIPTION The Carp routines are useful in your own modules because they act like die() or warn(), but with a message which is more likely to be useful to a user of your module. In the case of cluck, confess, and longmess that context is a summary of every call in the call-stack. For a shorter message you can use carp, croak or shortmess which report the error as being from where your module was called. There is no guarantee that that is where the error was, but it is a good educated guess. <continues here>

The "use" directive makes sure the requested module is loaded at compile time. If there is a list following the module name, that list represents symbols that will be exported from the module to be used (imported) in your program. In the Carp.pm module, one of the functions is called croak. If requested, the user can call the croak function without fully qualifying the symbol name with the :: syntax (Carp::croak).

The following example illustrates how to create a module in a separate .pm file and use the module in another program. Although this module itself looks like any other package, it must additionally include the Exporter module, the @ISA array, and the @EXPORT array for it to really behave as a module. The ability to export specific symbols to other programs and to import other modules is what differentiates a module from a .pl file. To see a skeletal module for creating modules for CPAN, see "Creating Extensions and Modules for CPAN with the h2xs Tool" on page 395.

|

Code View: (The Me.pm Module) 1 package Me; 2 use strict; use warnings; 3 require 5.6; # Make sure we're a version of Perl no # older than 5.6 4 require Exporter; # Exporter.pm allows symbols to be imported # by others 5 our @ISA=qw(Exporter); # ISA is a list of base packages needed # by this module 6 our @EXPORT_OK=qw(hello goodbye ); # List of your subroutines # to export 7 sub hello { my($name)=shift; print "Hi there, $name.\n" }; 8 sub goodbye { my($name)=shift; print "Good-bye $name.\n";} 9 sub do_nothing { print "Didn't print anything. Not in EXPORT list\n";} 1; ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– #!/usr/bin/perl # Program name: main.perl 10 use lib ("/home/ellie/Modules"); # A pragma to update @INC. 11 use Me qw(hello goodbye); # Import package 12 &hello ("Daniel"); 13 &goodbye ("Steve"); 14 &do_nothing; # This was not on the Export list # in Me.pm so cannot be imported unless # explicitly with &Me::do_nothing (Output) 12 Hi there, Daniel. 13 Good-bye Steve. 14 Undefined subroutine &main::do_nothing Explanation

|